Teenage Baseball Pitchers at Risk for Permanent Shoulder Injury

Released: October 14, 2014

At A Glance

- Excessive overhead throwing may lead to a newly identified shoulder injury.

- As a result of the injury, developing shoulder bones may not fuse properly and rotator cuff tears may occur later in life.

- Young baseball pitchers should not throw more than 100 pitches per week.

- RSNA Media Relations

1-630-590-7762

media@rsna.org - Linda Brooks

1-630-590-7738

lbrooks@rsna.org - Emma Day

1-630-590-7791

eday@rsna.org

OAK BROOK, Ill.—Young baseball pitchers who throw more than 100 pitches per week are at risk for a newly identified overuse injury that can impede normal shoulder development and lead to additional problems, including rotator cuff tears, according to a new study published online in the journal Radiology.

The injury, termed acromial apophysiolysis by the researchers, is characterized by incomplete fusion and tenderness at the acromion. The acromion, which forms the bone at the top or roof of the shoulder, typically develops from four individual bones into one bone during the teenage years.

"We kept seeing this injury over and over again in young athletes who come to the hospital at the end of the baseball season with shoulder pain and edema at the acromion on MRI, but no other imaging findings," said Johannes B. Roedl, M.D., a radiologist in the musculoskeletal division at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia.

To investigate the unexplained pain, Dr. Roedl and a team of researchers conducted a retrospective study of 2,372 consecutive patients between the ages of 15 and 25 who underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for shoulder pain between 1998 and 2012. The majority of the patients, which included both males and females, were baseball pitchers.

"Among high school athletes, pitching is the most common reason for shoulder pain," Dr. Roedl said.

Sixty-one of the patients, (2.6 percent) had pain at the top of the shoulder and an incomplete fusion of the acromion but no other findings. The patients were then age and sex-matched to patients who did not have the condition to form a control group.

Pitching history was available for 106 of the 122 patients included in the study. Through statistical analysis, the researchers found that throwing more than 100 pitches per week was a substantial risk factor for developing acromial apophysiolysis. Among the patients with this overuse injury, 40 percent threw more than 100 pitches per week, compared to 8 percent in the control group.

"We believe that as a result of overuse, edema develops and the acromion bone does not fuse normally," Dr. Roedl explained.

All 61 injured patients took a three-month rest from pitching. One patient underwent surgery while the remaining 60 patients were treated conservatively with non-steroidal pain medication.

Follow-up MRI or X-ray imaging studies conducted a minimum of two years later after the patients turned 25 were available for 29 of the 61 injured patients and for 23 of the 61 controls. Follow-up imaging revealed that 25 of the 29 patients (86 percent) with the overuse injury showed incomplete fusion of the acromion, compared to only 1 of the 23 (4 percent) controls.

"The occurrence of acromial apophysiolysis before the age of 25 was a significant risk factor for bone fusion failure at the acromion and rotator cuff tears after age 25," Dr. Roedl said.

Twenty-one of the 29 patients with the overuse injury continued pitching after the rest period, and all 21 showed incomplete bone fusion at the acromion. Rotator cuff tears were also significantly more common among this group than in the control group (68 percent versus 29 percent, respectively). The severity of the rotator cuff tears was also significantly higher in the overuse injury group compared to the control group.

"This overuse injury can lead to potentially long-term, irreversible consequences including rotator cuff tears later in life," Dr. Roedl said.

Dr. Roedl and his colleagues suggest teenage and young adult pitchers limit the number of pitches thrown in a week to 100. The American Sports Medicine Institute currently recommends that baseball pitchers between 15 and 18 years of age play no more than two games per week with 50 pitches per game.

"Pitching places incredible stress on the shoulder," Dr. Roedl said. "It's important to keep training in the moderate range and not to overdo it."

Dr. Roedl pointed out that many successful professional baseball pitchers played various positions, and even other sports, as young athletes and thereby avoided overuse shoulder injuries.

"More and more kids are entering sports earlier in life and are overtraining," he said. "Baseball players who pitch too much are at risk of developing a stress response and overuse injury to the acromion. It is important to limit stress to the growing bones to allow them to develop normally."

Acromial Apophysiolysis: Superior Shoulder Pain and Acromial Nonfusion in the Young Throwing Athlete." Collaborating with Dr. Roedl were William B. Morrison, M.D., Michael G. Ciccotti, M.D., and Adam C. Zoga, M.D

Radiology is edited by Herbert Y. Kressel, M.D., Harvard Medical School, Boston, Mass., and owned and published by the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. (http://radiology.rsna.org/)

RSNA is an association of more than 53,000 radiologists, radiation oncologists, medical physicists and related scientists, promoting excellence in patient care and health care delivery through education, research and technologic innovation. The Society is based in Oak Brook, Ill. (RSNA.org)

For patient-friendly information on MRI of the shoulder, visit RadiologyInfo.org.

Images (.JPG and .TIF format)

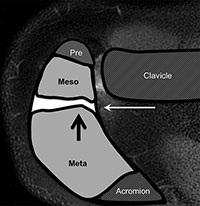

Figure 1. Anatomy of the acromion and fusion of the acromial apophyses (ossification centers).

The acromion bone of the shoulder develops by fusion of three ossification centers (apophyses) including the meta-acromion, meso-acromion, and pre-acromion which are depicted in this figure. The most relevant are the two largest apophyses, the meta-acromion (black arrow) and the meso-acromion. Edema and incomplete fusion (white arrow) between these two apophyses in patients younger than 25 years is termed acromial apophysiolysis. When nonfusion persists beyond the age of 25 years, the term os acromiale has been used in the literature.

High-res (TIF) version

(Right-click and Save As)

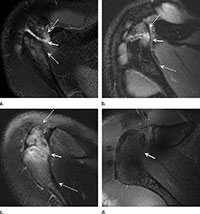

Figure 2. Examples of acromial apophysiolysis.

(a) 18-year-old baseball pitcher with acromial apophysiolysis including non-fusion (solid arrow) at the acromion and mild edema (dashed arrows). (b) 15-year-old softball player with acromial apophysiolysis including incomplete fusion at the acromion (solid arrow) and moderate edema (dashed arrows). (c) 20-year-old patient with acromial apophysiolysis including incomplete fusion at the acromion (solid arrow) and severe edema (dashed arrows) (d) 23-year-old patient from the control group of the study with normal complete fusion and no edema at the acromion.

High-res (TIF) version

(Right-click and Save As)

Figure 3. Longterm sequela of acromial apophysiolysis.

(a) Acromial apophysiolysis including incomplete fusion (solid arrow) at the acromion and with moderate edema (dashed arrows) in an 18-year-old male pitcher. (b) Follow-up image in the same patient as in (a) 7 years later at age 25 years after quitting pitching shows complete fusion (solid arrow) and resolution of the previously seen edema at the acromion (dashed arrows). (c) Acromial apophysiolysis including an unfused physis (solid arrow) and severe edema at the acromion (dashed arrows) in a 17-year-old female softball pitcher. (d) Follow-up image in the same patient as in (c) 9 years later at age 26 years after continued softball playing demonstrates unchanged nonfusion at the acromion (solid arrow) and development of an os acromiale with severe edema (dashed arrows).

High-res (TIF) version

(Right-click and Save As)